Monday, January 31, 2011

The Tainted History Of The ILGWU

Posted by David Ballela at 2:04 PM 0 comments

Labels: garment industry

Sunday, January 30, 2011

Memories Of The Rag Trade In Save The Tiger, 2

a clip from an excellent movie starring Jack Lemmon and Jack Gilford

from wikipedia

Save the Tiger is a 1973 film about moral conflict in contemporary America. It stars Jack Lemmon, Jack Gilford, Laurie Heineman, William Hansen, Thayer David, Lara Parker and Liv Lindeland. The film is adapted from the novel of the same title by Steve Shagan, (the first book by the author of The Formula and other thrillers, and generally regarded to be his most successful novel by literary standards).

Jack Lemmon plays Harry Stoner, an executive at a Los Angeles apparel company on the edge of ruin. Throughout the film, Stoner struggles with the complexity of modern life versus the simplicity of his youth. He longs for the days when pitchers wound up, jazz filled the air, and the flag was more than a pattern to put on a jock-strap. He wrestles with the guilt of surviving the war and yet losing touch with the ideals for which his friends died. To Harry Stoner, the world has given up on integrity, and threatens to destroy anyone who clings to it. He is caught between watching everything he has worked for evaporate, or becoming another grain of sand in the erosion of the values he once held so dear.

Posted by David Ballela at 12:15 PM 0 comments

Labels: garment industry

Memories Of The Rag Trade In Save The Tiger

a clip from an excellent movie starring Jack Lemmon and Jack Gilford

from wikipedia

Save the Tiger is a 1973 film about moral conflict in contemporary America. It stars Jack Lemmon, Jack Gilford, Laurie Heineman, William Hansen, Thayer David, Lara Parker and Liv Lindeland. The film is adapted from the novel of the same title by Steve Shagan, (the first book by the author of The Formula and other thrillers, and generally regarded to be his most successful novel by literary standards).

Jack Lemmon plays Harry Stoner, an executive at a Los Angeles apparel company on the edge of ruin. Throughout the film, Stoner struggles with the complexity of modern life versus the simplicity of his youth. He longs for the days when pitchers wound up, jazz filled the air, and the flag was more than a pattern to put on a jock-strap. He wrestles with the guilt of surviving the war and yet losing touch with the ideals for which his friends died. To Harry Stoner, the world has given up on integrity, and threatens to destroy anyone who clings to it. He is caught between watching everything he has worked for evaporate, or becoming another grain of sand in the erosion of the values he once held so dear.

Posted by David Ballela at 12:13 PM 0 comments

Labels: garment industry

The Uprising Of The 20,000

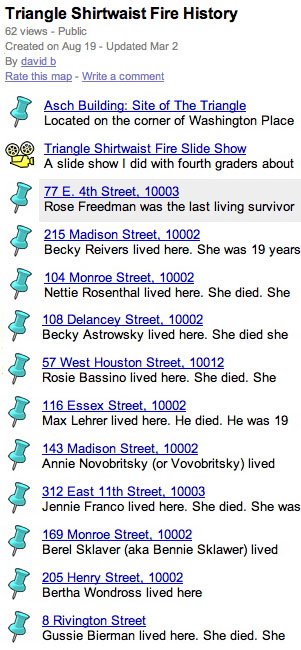

originally posted on knickerbocker village on Nov. 9th, 2009

Today is the 100th anniversary of the Uprising of the 20,000. Above is the clip from I'm Not Rappaport. from the ILGWU wiki page.

On November 22, 1909, New York City garment workers gathered in a mass meeting at Cooper Union to discuss pay cuts, unsafe working conditions and other grievances. After two hours of indecisive speeches by male union leaders, a young Jewish woman strode down the aisle and demanded the floor. Speaking in Yiddish, she passionately urged her coworkers to go out on strike. Clara Lemlich, a fledgling union organizer, thus launched the 'Uprising of the 20,000,' when, two days later, garment workers walked out of shops all over the city, effectively bringing production to a halt.

A dramatization of that incident, re-created in the Hollywood film I'm Not Rappaport, movingly introduces the documentary portrait CLARA LEMLICH, which recounts the life of the Ukrainian-born immigrant. Like thousands of other young women, Lemlich found work in a clothing factory where she worked 7 days a week, from 60 to 80 hours, for less than a living wage. In her burning desire to get an education Lemlich read widely and organized a study group to discuss women's problems. Her success as an organizer, which included numerous arrests and beatings by strikebreakers, eventually led to her election to the executive board of the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union.

Lemlich's story is movingly recounted through interviews with her daughter and grandchildren, dramatic readings from her diary, family photos and archival footage, strike songs in Yiddish, an interview with labor historian Alice Kessler-Harris, a visit to the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, and excerpts from silent films of the era.

In addition to its biographical portrait, CLARA LEMLICH also chronicles the historic ILGWU strike, which demonstrated to the male leadership that women could be good union members and strikers. The union negotiated a settlement in February 1910 that led to improvements in wages as well as working and safety conditions. One of the companies that refused to sign the agreement was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, where, the following year, a fire resulted in the death of 146 young women, a tragedy that galvanized public support for the union movement

Posted by David Ballela at 10:01 AM 1 comments

Friday, January 28, 2011

Max Blanck's Tainted Epilogue

blanck-epilogue

contained within the document are pages from David von Drehle's book and google street views of where Max Blanck lived in 1900 and 1910. I don't think amyone would want to chalk those locals.

Posted by David Ballela at 1:21 PM 0 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Look For The Union Label...The Tainted History of The Triangle Shirtwaist Company

The Triangle Waist Company, New' York, was last week temporarily enjoined from using on its goods a label declared to be imitative of that of the National Consumers' League.

This is the same Triangle Waist Company in whose factory a fire killed 140 girls in 1911—it being afterward proved that doors leading from the factory, which was on the ninth floor of a loft building, had been locked.

It is the same Triangle Waist Company that, two years and six months later, was again convicted of having its doors locked, and whose head, Max Blanck, was given the minimum fine on the ground that he was a first offender.

The National Consumers' League authorizes manufacturers to use its label only after investigation has showed that the goods on which it is to be used are made under "clean and healthful" conditions. The Triangle company has never been authorized to use its label.

The label declared to be an imitation, which is here reproduced, was first discovered by the Consumers' League last spring on some goods in a Boston department store. The buyer of the store told a representative of the league that he was buying waists with the league's label on.

It required several months to trace the label to the Triangle Waist Company. An effort was then made to induce employes of the Triangle company to sign' affidavits declaring that the suspicious label was used by that concern. The employes' fear of being blacklisted among manufacturers frustrated this.

A few weeks ago' the Consumers'

League served the Triangle Company with a summons and complaint in an action for a permanent injunction and with motion papers for an injunction pending trial, until final decision could be reached, which will not be till next winter. The league's action is based on the common law rules governing unfair trade and unfair competition. The label is not a registered trademark.

The Triangle company, in its answer, admitted the use of the label, but declared that it had not intended to imitate any other label, and denied knowledge of the existence of the National Consumers' League. It also questioned the right of the league to sue, on the ground that the league is not a manufacturer of shirt waists with a financial stake involved in the protection of its label, and therefore cannot invoke the common law rules cited above.

In granting the temporary injunction. Justice Leonard A. Giegerich, of the Supreme Court of New York county, declared that he was satisfied that the Triangle Company's label was an illegal imitation. While it is felt that this decision strongly presages the granting of the permanent injunction, it is pointed out that the question of law involved is a new one.

The nearest parallel case is said to be that of labor unions, which have been granted injunctions in behalf of their labels. These decisions have, however, rested on the ground that the members of the union had a financial stake, i. c. their wages, involved.

The league contends that it is but a logical extension of the "financial stake" theory to protect it in the use of its label. In anticipation of just this point, however, Bertha Rembaugh, attorney for the league, joined both a manufacturer of waists and a retail store in the action against the Triangle Company. These concerns, it is contended, have a financial interest in the protection of the league's label because their own sales would be affected by its fraudulent imitation. Should the case go against the league, it is feared that the opening which this would give to the imitation of the league's label would go far to destroy the effectiveness of the league's label work.

Posted by David Ballela at 10:43 AM 0 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Frank H. Sommer: Unsung Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Hero

Posted by David Ballela at 10:00 PM 1 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Fannie Lansner: Unsung Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Hero

Another forgotten hero is Fannie Lansner, whose selfless actions were headlined by on page two of The New York Evening Telegram of Monday March 27, 1911: “Heroic Young Forewoman Loses Her Life to Save Others from Death in Flames: Miss Fannie Lansner Guides Girls to Safety Until Her Own Escape Is Cut Off; THEN LEAPS FROM WINDOW TO DEATH ON PAVEMENT; Calm in Midst of Peril, She Does Her Utmost to Calm Panic-Stricken Women to the Last”.

“Speaking both Yiddish and English to the girls who were huddled about her, all crying and screaming, Miss Lansner guided some of them down the stairways and kept others waiting for the elevator,” the Evening Telegram reported. “Trip after trip of the elevator was made and Miss Lansner remained on the floor, and several girls begged her to go with them down the elevator, Miss Lansner said she would be ‘all right, and told them to go out as quickly as possible.”

In another account on March 30, 1911, The Hartford Courant wrote, “A number of the employees testified at the district attorney’s office to the heroism of Fannie Langner [sic], who rushed scores of girls from the eigth floor to the elevator and superintended crowding them into the car. Again and again she went into the smoke filled cutting rooms and brought out girls. Finally, she fell, exhausted and perished.”

According to the 1910 Census, Fannie live at 78 Forsyth Street.

Posted by David Ballela at 9:33 AM 0 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Saturday, January 22, 2011

Edward Croker: Fighting Fire, Boys' Life January 1914

Posted by David Ballela at 11:56 AM 0 comments

Labels: edward croker, triangle shirtwaist fire

Edward Croker: Fire Chief During Triangle Shirtwaist Tragedy

edward-croker

I too would have assumed that a Tammany relative would have had questionable abilities and/or motives. Boats against the current feels he was a man worthy of praise

All through elementary and secondary school, I heard nothing about this crucial event in American history. In fact, the first time I came across it was in the superlative chapter on Alfred E. Smith in Robert A. Caro’s biography of Robert Moses, The Power Broker.

I would hope that modern texts remedy this problem, but I doubt it—kids nowadays are lucky they can figure out in which century the Civil War occurred. In certain ways, however, I believe that March 25, 1911 should be committed to memory as surely as July 4, 1776.

Both dates, in their ways, marked a movement away from heavy-handed control by an elite and toward greater freedom—in one case, for white American males of property; in the later one, for the economically oppressed laborer, frequently female and foreign-born.

So, if I were to design a syllabus to teach this event, what would I choose?

Well, I’d start with So Others Might Live, a fine account of New York’s Bravest by journalist-historian Terry Golway. The section on the Triangle fire is short—only a half-dozen pages—but they give an excellent précis for the conditions that led to the blaze and the Fire Department’s helpless anger in combating it.

It also discusses an Irish-American Cassandra, department head Edward Croker, a chief as blunt as he was fearless, who, for his repeated warnings about high-rise office and factory buildings, had to endure constant smearing by business interests for being the nephew of past Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker—until events proved him right.

Posted by David Ballela at 11:45 AM 0 comments

Labels: edward croker, triangle shirtwaist fire

Friday, January 21, 2011

Joseph Zito: Hero Of The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

Posted by David Ballela at 5:31 AM 0 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Labor History In NY Schools: It's Not Happening

triangle-i-ITALY

I don't know how the reporter of this story got this impression just by observing one class at last year's ceremony!

If you are a kid and go to a public school in New York City you will probably know this date by heart because every year there will be a field-trip with your classmates to the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street; under the rain or the sun, or fighting against the wind, you would proudly put on a red fire-fighter hat holding your teacher's hand or curiously looking at the much older NYU students crowding around campus, walking by....I've contacted about a dozen schools to volunteer my services to teach about the Triangle without any success. I'm a former dept of education history grant coordinator and a district technology teacher trainer. I have materials and lesson plans, as the expression goes, "up the wazoo." The principal down the block from my home, a nice guy who I knew when he was a rookie teacher, didn't even know what the fire was, nor did his leadership academy trained AP. In addition there appear to be organizations created to educate about the fire but there is no apparent sign of that being done other than to pad a resume or make a fast buck.

Posted by David Ballela at 4:38 AM 0 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Mary Fell: Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Poet

.....Out of the darkness of the sweatshop these poems exist. Although spirituality and workers consciousness are not often juxtaposed, I want to recognize the interplay of secular and religious literary tropes as evidence of a secular spirituality calling for economic justice. Consider the element of ritual in these poems. This fire poetry calls to the reader as the events called to the writers to engage in a ceremony of mourning, remembrance and continued struggle. I imagine these poets--however diasporically situated--as conveying a women's minyan--individual voices coming together to engage in a ceremony of definition.19 Each poem is a kind of midrash on the event, a commentary on and dialogue with other voices across time. These poets do not attempt to compensate for the fire, or replicate the event. They take on the burden of mourning and memory, and the poems become a kind of Kaddish, a secular prayer evoked out of class and gender memory, and of shared knowledge of the dangers of unprivileged work. The poems are a symbolic action and a public utterance by the survivors, all the symbolic daughters of the Triangle workers. Their poetry is not a praisesong to death or to God, but a way to use language (replete with religious allusions) as a force against historical oblivion. Mary Fell begins her beautiful nine part fire poem with: "Havdallah"This is the great divide

by which God split

the world:

on the sabbath side

he granted rest,

eternal toiling

on the workday side.

But even one

revolution of the world

is an empty promise

where bosses

where bills to pay

respect no heavenly bargains.

Until each day is ours

let us pour

darkness in a dish

and set it on fire,

bless those who labor

as we pray, praise God

his holy name,

strike for the rest.

about Mary Fell

Mary Fell (born September 22, 1947 Worcester, Massachusetts) is an American poet and academic.She currently teaches at Indiana University

The city of Worcester has always had its fingers in all areas of the arts and literature. It has been the home and the resting place of many great writers and poets. When most think of the poets in Worcester, names like Kunitz, Bishop, or Olson surface, but what has kept that fire alive has been the less known, less published poets of this generation. Mary Fell was born in and grew up in Worcester, and she is one of these poets.

Fell was born to Elizabeth “Betty” and Paul Fell in Worcester City Hospital on September 22, 1947. Betty had come from Fairhaven, Massachusetts to Worcester during the Great Depression in order to find work. Once there she met and married Paul, an Irish American “Worcester kid.” Paul worked as a custodian in Worcester, was on the city Retirement Board, and had become chairman by the time he passed away.

Fell grew up mostly in Main South Worcester with her older brother Paul. She attended Downing Street School for kindergarten, and then went to St. Peter’s through high school. Though their mother was a Protestant she sent her children to St. Peter’s because at the time children had to come home for lunch at Downing St., but St. Peter’s allowed them to bring their lunch. This was important because her mother needed to work and couldn’t be home for the children at lunchtime.

Fell spent most of her childhood days in Main South at the St. Peter’s School and church and in the local landmarks like the Park Theater, Coes Pond, Beaver Brook, and Crystal Park. Because they never owned a car, any family excursions were taken on the bus. She remembers downtown Worcester being magical with ice skating in Elm Park, and the Charity Circus at the Auditorium. .......After high school Fell attended Worcester State College and majored in English. Throughout most of her childhood the children she encountered were just like her “second or third generation Americans who were rarely ethnically diluted by more than half – Irish or Polish or Italian.” It wasn’t until she attended college that she was introduced to many of the other ethnicities and people of the world. College in the 1960s meant the anti-war movement, free speech, civil rights, and feminism. These were all accepted as part of daily life.

It was in college that Fell began writing poetry. She studied, loved and tried to write it. However, she felt that it wasn’t possible for someone like her to write poetry. It wasn’t until the Women’s Movement in the 1970s that she realized that she could write poetry about the things she wanted to write about: mostly, the life and people she had grown up with. This movement made Worcester a great place for a budding poet in the 70s. The Worcester County Poetry Association brought many of Fell’s heroes to Worcester for readings. Poets like Adrienne Rich, Denise Levertov, Ann Sexton, Muriel Rukeyser, Robert Bly, Michael Harper, Galway Kinnell all came to Worcester during this time....

Posted by David Ballela at 3:06 AM 0 comments

Labels: mary fell, triangle shirtwaist fire

Sunday, January 16, 2011

Tainted Testimony At Triangle Shirtwaist Trial

Triangle Black Witness

The testimony of a porter named William Harris is highlighted. It appears the veracity of his statements were questionable. It's strange that the address given by Harris is the address of another porter from the factory named Reginald Williamson. The Times' reporter's transcription of the testimony smacks of yellow journalism.

I'm sure other immigrants who testified used broken English, yet their transcriptions seemed to have been treated more delicately.

Posted by David Ballela at 8:41 PM 0 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Rose Pesotta: 1930

more of her biography from the Jewish Women's Encyclopdia

Shortly before her death, Rose Pesotta was asked how she would live her life if she could live it over again. She replied, “I have no regrets of my chosen path of the past. I would choose the same path, trying perhaps to avoid some of the mistakes of the past. But always having the vision before me—in the words of Thomas Paine, ‘The world is my country. To do good is my religion.’” The sweeping idealism of that statement tells us much about Pesotta, anarchist, labor activist, immigrant, internationalist. Known primarily as one of the first female vice presidents of the international ladies garment workers union (ILGWU), Pesotta saw her union organizing as an opportunity to fulfill the anarchist mandate “to be among the people and teach them our ideal in practice.”

Rose Pesotta was born in 1896, the second of eight children, into a middle-class family in Derazhnya, a railroad town in the Russian Ukraine. Her father, Itsaak Peisoty, was a grain merchant, and her mother, Masya, was active in the family business. Pesotta attributed her lifelong concern for social justice to her “dynamic and unconventional” father, but seemed unaware that the shtetl tradition of women’s work outside the home represented by her mother may have also facilitated her career.

Pesotta attended Rosalia Davidovna’s school for girls, with its Russian curriculum and its clandestine classes in Jewish history and Hebrew. After two years at the school, she was needed at home to help care for her siblings, and home tutoring replaced formal schooling. But her political apprenticeship in one of the many leftist groups in the Russian Pale of Settlement was as important as her formal education. She joined her older sister, Esther, in the local anarchist underground. The group’s discussion of well-known leftists Pyotr Kropotkin, Mikhail Bakunin, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and the political activities of young radicals, opened a window on the possibilities of a wider world.

Her parents’ plan to marry her to an ordinary village boy precipitated her decision to join her sister in America. In 1913, her parents gave her permission to embark for the New World. Once in New York, Pesotta began working in various shirtwaist factories, and struggled to learn English. Soon, she joined Local 25 of the ILGWU. The local became a base for her union career. In 1915, she helped the local form the first education department in the ILGWU, and in 1920 she was elected to Local 25’s executive board. In 1922, Pesotta completed the program at the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Workers, and between 1924 and 1926, she was a student at Brookwood Labor College. During the 1920s, she played a key role in the union’s chronic struggles with communists. Grateful union officials recognized Pesotta’s contributions by appointing her as an organizer in the late 1920s.

Pesotta brought a charismatic personality, boundless energy, and a unique ability to empathize with the downtrodden to the organizing field. In 1933, she spearheaded the Dressmakers General Strike in Los Angeles in the face of antipicketing injunctions, hired thugs, and communist dual unions. She mobilized the largely Mexican labor force through Spanish-language radio broadcasts and ads in ethnic newspapers. Although the strike was not successful, Pesotta’s leadership established her as one of the most gifted organizers of the union.

Pesotta’s visibility in California led to her election in 1934 as a vice president of the ILGWU, serving on the general executive board. Pesotta was conflicted about her ten years of service in that position. Sexism and a loss of personal independence continually troubled her, until she finally resigned from the position in 1942.

Between 1934 and 1944, though, Pesotta was one of the most successful organizers in the United States. She carried the union message to workers in Puerto Rico, Detroit, Montreal, Cleveland, Buffalo, Boston, Salt Lake City, and Los Angeles. On loan from the ILGWU to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), she joined the great labor upheavals of the 1930s in Akron, Ohio, and Flint, Michigan. In 1944, Pesotta refused a fourth term on the CIO General Executive Board, with a brief critical statement that “one woman vice president could not adequately represent the women who now make up 85 percent of the International’s membership of 305,000.”

Following her resignation from union office, Pesotta published two memoirs: Bread upon the Waters (1945) and Days of Our Lives (1958). She worked briefly for the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League and for the American Trade Union Council for the Histadrut, Israel’s labor organization. But she supported herself during those years largely as a factory operative. Her life, in a sense, had come full circle—she embraced what she called “the freedom of a plain rank and file member of the union.”

Anarchism and Judaism are key to understanding Pesotta’s identity and sense of self. Although first introduced to anarchist philosophy in Europe, Pesotta found community and support for her libertarian beliefs in the alternative culture of American anarchism. Anarchism was her ethical center. It celebrated the inherent goodness of the individual and rejected private property, the state, and authority. Like emma goldman and other women attracted to the movement, Pesotta found support for a sexually free life-style embedded in anarchist tenets of personal freedom. She was secretary of the anarchist paper The Road to Freedom and was a key member of the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee.

For Pesotta, anarchism was inextricably enmeshed with Jewish culture and communities. Although not religiously observant, Pesotta always identified herself as Jewish. The Holocaust and the foundation of Israel deepened her sense of herself as a Jew. It seems ironic that her second memoir casts Judaism in a central role after a lifetime spent in secular activism and outside of the family roles critical to Jewish practice. Closer scrutiny reveals the congruence between Pesotta’s idealized past and her American life. In her books, her need to understand “external power relationships” as a Jew in czarist Russia meshed neatly with the Jewish labor union in tension with American culture.

In the fall of 1965, Pesotta was diagnosed with cancer of the spleen. Quietly she resigned from her job and went to Miami to “recuperate in the sun.” On December 4, 1965, she died alone in a Miami hospital.

Posted by David Ballela at 4:49 PM 0 comments

Labels: google maps, rose pesotta

Rose Pesotta's Bread Upon The Waters

Posted by David Ballela at 4:27 PM 0 comments

Labels: rose pesotta

Rose Pesotta: Labor Hero

an excerpt from Rose's biography by Jane Leeder

Lisa Luchkovsky, who is mentioned (and pictured on page 4) was my wife's great aunt

pesotta

Born Rakhel Peisoty or Peisotaya, 1896 - Ukraine, died 1965 - US

Few female Jewish immigrants to the U.S. have led lives as dynamic and eventful as Rose Pesotta. She was born Rakhel Peisoty in a Ukrainian shtetl, Derazhnia1 and became a rebel early in life, sympathizing with the anti-Czarist revolutionary movement, People's Will, before she became a teenager. At age 16 she immigrated to the US to escape an arranged marriage and to join her older sister. Their father was murdered in a pogrom in 1919, perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists.

Arriving in New York in 1913, Rakhel Peisoty became Rose Pesotta in the confusion of the immigration offices on Ellis Island. Rose’s sister found her a job in a shirtwaist factory organized by Local 25 International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU). Before long she became an organizer for the union. She participated in many strikes and was the first woman elected to the executive board of the local, where she established one of the first worker education programs. Meanwhile, she learned English at night school and continued her studies at the Bryn Mawr School for Workers in Industry, the Rand School of Social Science and the Wisconsin Summer School for Workers. In 1926 she graduated from the Brookwood Labor College, which existed from 1921 to 1937 as a residential school for social activists belonging to the non-Communist left.

In 1933, she became a general organizer for the ILGWU and the next year she was elected a vice-president, the first woman to hold such a high post. She accepted the position, though she strongly believed that “the voice of a solitary woman on the General Executive Board would be a voice lost in the wilderness.” Her prediction proved correct as no other women were chosen, even as their percentage of the general membership rose to 85% by the 1940s.

Pesotta was an anarchist. She attended anarchist conferences, wrote for its press and opposed World War I as an imperialist war. She was befriended by fellow anarchist, Emma Goldman and nearly shared her fate in being deported. In 1919, Pesotta was arrested in the notorious Palmer raids and held for deportation as a subversive alien. Unlike Goldman, she was able to establish her citizenship. Her fiancé was not as lucky. He was deported to the Soviet Union along with Goldman and she never saw him again. Pesotta was again arrested again in 1927 for protesting against the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti.

Pesota had a flair for the dramatic. During a strike in Los Angeles against a manufacturer of sportswear, she dressed some of the young female workers in evening gowns and had them march in front of a posh hotel wearing their picket signs. She made sure the press was there. The favourable publicity this event received softened the position of the employer, who did not want to be seen as the exploiter of beauty queens. The strike ended in a victory for the ILGWU.

Pesotta was such an outstanding union organizer that the ILGWU loaned her to the union confederation the C.I.O. for its organizing drives in heavy industry. In the late 1930s, she assisted the rubber workers during their sit-down strike at Goodyear in Akron, Ohio and the auto workers during their sit-down at General Motors in Flint, Michigan. Despite language and cultural differences, she also achieved success organizing for the ILGWU among Mexican workers in Los Angeles, French Canadians in Quebec and in Puerto Rico.

Her union activism took its toll, both physically and emotionally. She was beaten so seriously by anti-union thugs that she suffered permanent hearing loss. Constantly on the move, she suffered from loneliness and was unable to establish a stable personal life. In 1940, she resigned from the leadership of the ILGWU, disillusioned with male domination of the union after David Dubinsky, long-time president of the union, didn't respond to her complaints about being the only woman on the executive board. She returned to the rank-and-file as a shop worker, where she vigorously supported the Allies in World War II. At the same time, she opposed the no-strike pledge taken by the leadership of both the AFL and CIO, because it tied the hands of workers while employers benefited from rising prices and profits.

Pesotta's life took a different turn with the onset of World War II. Shaken by the news of the slaughter of European Jewry, including many of her relatives, she joined the B'nai Brith Anti-Defamation League and began speaking throughout the country against anti-Semitism and racism. After the war, she traveled to Poland and visited the Majdenek concentration camp, where she met with survivors. She worked tirelessly to resettle them in the U.S.

In her earlier years, she had an ambivalent attitude toward her Jewishness. Echoing Thomas Paine, she declared, “The world is my country and to do good is my religion.” But the impact of the Holocaust turned her into a Zionist. She became Midwest Director of the American Trade Union Council for Histadrut and from then on identified with the Labour Zionist movement until the end of her life in 1965.

Pesotta also distinguished herself as an advocate for civil rights for African Americans. During her entire public life, she remained true to the lesson she learned from a private tutor back in the Ukraine: “The people come first. It is their actions that bring about changes in society.”

Pesotta had literary interests as well. She wrote a novel about a Yeshiva student who became a revolutionary and two volumes of memoirs, Bread Upon the Waters (1944) and Days of Our Lives (1958). She dedicated the second volume to the memory of the Jewish civilization destroyed by the Nazis.

Shortly before her death, Rose Pesotta was asked how she would live her life if she could live it over again. She replied, “I have no regrets of my chosen path of the past. I would choose the same path, trying perhaps to avoid some of the mistakes of the past. But always having the vision before me—in the words of Thomas Paine, ‘The world is my country. To do good is my religion.’” The sweeping idealism of that statement tells us much about Pesotta, anarchist, labor activist, immigrant, internationalist. Known primarily as one of the first female vice presidents of the international ladies garment workers union (ILGWU), Pesotta saw her union organizing as an opportunity to fulfill the anarchist mandate “to be among the people and teach them our ideal in practice.”

Posted by David Ballela at 3:50 PM 0 comments

Labels: rose pesotta

Friday, January 14, 2011

Thomas Horton: Unsung Triangle Fire Hero From Harlem?

Thomas Horton is listed as a porter. In an article written about the fire he evidently performed heroically under horrific circumstances. I would suggest he was more than just a porter and if my search of the 1910 census is correct he may have had engineering skills necessary to operate and maintain the building's elevators. The Thomas Horton above is the only "colored" Horton I found living in New York. He was an assistant engineer in an office building. Born in North Carolina, he would have logically followed the migratory pattern to the north to find better jobs at the time as well as housing in Harlem.

Below a reference to him in a 1957 American Heritage article

On the Greene Street side of the Asch building, the freight elevators “ran until they wouldn’t run.” “We were putting in the switch cables till they were overrun with water,” Thomas Horton, the Negro porter recalls. “They stuck. The circuit-breakers were blowing out.”h/t to Jane Fazio, Michael Hirsch and Prof Alan Singer

As Horton toiled grimly in the basement to keep the motors going, the elevator operators opened their doors at random in the blinding smoke, making desperate guesses as to floor openings. Fire streamed into the shafts, flame bit at the cables, and the girls jumping in suicidal fright jammed the operation of the cars. Nineteen bodies were found later wedged between the car and shaft in one of the Greene Street freight elevator wells.

Posted by David Ballela at 8:18 PM 2 comments

Labels: triangle shirtwaist fire

Fanny Breslow

The Free Voice of Labor: The Jewish Anarchists is a 1980 documentary by Steve Fischler and Joel Sucher of Pacific Street Films. It memorializes the story of the Yiddish anarchist newspaper Fraye Arbeter Shtime, and the Jewish anarchist movement of the early 20th century. The movie contained a short interview with a very young Joe Conason. Paul Avrich was a consultant on the film. As of 2006, AK Press has begun distributing it as part of a double DVD release with Anarchism in America, named after the latter.This an excerpt from part 2

Posted by David Ballela at 1:04 AM 0 comments

Thursday, January 13, 2011

The ILGWU: August 1, 1938, part 2

Life Ilgwu 1938

Displayed at the Grey Art Gallery in remembrance of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire 100th anniversary. I was curious to find out whether Yetta Henner was still alive. I assumed she married Hy Stofsky, her boyfriend in the article. Sadly, a Yetta Stofsky passed away in 1995 in Florida at the same age Yetta Henner would have been. Living where she did on Rivington Street her family may have known the Greenglass family from around the corner. She was around the same age as Ethel.

Posted by David Ballela at 8:27 AM 0 comments

Labels: ILGWU, triangle shirtwaist fire

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

The ILGWU: August 1, 1938

Hansel Mieth (1909–1998) was a German-born photojournalist who worked on the staff of LIFE Magazine. She was best known for her social commentary photography which recorded the lives of working class Americans in the 1930s and 1940s.

She was born Johanna Mieth in Oppelsbohm, Germany, one of three daughters of a strict, religious family. She ran away from home at the age of 15 and did factory work before emigrating to the United States in 1930 to join her lover and fellow photographer Otto Hagel (1909–1973). The couple found themselves in the midst of the Great Depression and worked as migrant farm labourers for several years. During that time they began to photograph the brutal working conditions and suffering they saw around them, after acquiring a second-hand Leica camera. In San Francisco, Sacramento, and in the rural towns they worked in, they photographed the bitter labour strikes and the working homeless. They were involved with the San Francisco Film and Photo League during the early 1930s. They also became acquainted with working photographers and began to sell their own photographs to magazines.

In 1937 Mieth joined the staff of LIFE Magazine (only the second woman photographer to do so), and she and Otto (whom she married in 1940), moved to New York. He was then still a German citizen, so in order to escape internment during the Second World War the couple fled to a remote ranch near Santa Rosa in northern California. Mieth continued to accept photography assignments for LIFE, while Hagel never left the Singing Hills Ranch.

During the War Mieth photographed Japanese Americans who had been taken from their homes and interned by the Roosevelt government. In the early 1950s, the couple's refusal to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (where they would have been required to name names of their friends in the labour movement) led to Mieth's losing her job at LIFE, and to their being unofficially blacklisted. Shunned by their former friends, the couple retired to their ranch in California where they raised livestock and where Mieth took up painting. She died in Santa Rosa California in 1998.

Mieth's life story was told in a one-hour documentary titled Hansel Mieth: Vagabond Photographer,which aired on PBS' Independent Lens series in 2003.

The full archive of Hansel Mieth's work is located at the Center for Creative Photography (CCP) at the University of Arizona in Tucson, which also manages the copyright of her work.

Posted by David Ballela at 10:46 PM 0 comments

Labels: ILGWU

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Pins and Needles: Sing Me A Song With Social Significance

This is the song "Sing Me a Song With Social Significance", sung by Rose Marie Jun, from the 1962 revival cast of Pins and Needles.

Pins and Needles is a Broadway revue, written originally in 1937s. The revue was written, sponsored, and performed by the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, who held their union meetings at the Princess theater in New York City.

The cast members all had full time factory jobs in the garment industry, and thus could only rehearse during the night and on the weekends.

Pins and Needles used its voice to air strong pro-Union opinions, incorporating current events from its time. The show features light hearted and clever use of satire and spoof to poke fun of such things fascist dictators in Europe and snooty American bigots.

The American theatre historian and writer John Kenrick said of the show Pins and Needles "is the only hit ever produced by a labor union, and the only time when a group of unknown non-professionals brought a successful musical to Broadway."

I'm tired of moon songs, of star and of June songs,

They simply make me nap.

And ditties romantic drive me nearly frantic,

I think they're all full of pap.

History's making, nations are quaking,

Why sing of stars above?

For while we are waiting, father time's creating

New things to be singing of...

Sing me a song with social significance,

All other tunes are taboo.

I want a ditty with heat in it,

Appealing with feeling and meat in it.

Sing me a song with social significance,

Or you can sing till you're blue,

Let meaning shine from every line

Or I won't love you.

Sing me of wars, sing me of breadlines,

Tell me of front page news,

Sing me of strikes and last minute headlines,

Dress your observations in syncopation.

Sing me a song with social significance,

There's nothing else that will do.

It must get hot with what is what

Or I won't love you.

Sing me a song with social significance,

All other tunes are taboo,

I want a song that's satirical,

And putting the mere into miracle.

Sing me a song with social significance,

Or you can sing till you're blue,

It must be packed with social fact

Or I won't love you.

Sing me of crime and conferences martial,

Tell me of mills and of mines,

Sing me of courts that aren't impartial,

What's to be done with 'em? Tell me in rhythm.

Sing me a song with social significance,

There's nothing else that will do.

It must be dense with common sense

Or I won't love you.

Posted by David Ballela at 6:41 PM 0 comments

Labels: ILGWU, pins and needles

Pins and Needles: Doing The Reactionary Rag

It's darker than the dark bottomThe song is from the play Pins and Needles. About the production:

It rumbles more than the Rumba

If you think that the two-steps got 'em

Just take a look at this number

It's got that certain swing

That makes you wanna sing

Don't go left, but be polite

Move to the right

Doing the reactionary

Close your eyes to where you're bound

And you'll be found

Doing the reactionary

All the best dictators do it

Millionaires keep steppin' to it

The Four Hundred love to sing it

Ford and Morgan swing it

Hands up high and shake your head

You'll soon see red

Doing the reactionary

Don't go left, but be polite

Move to the right

Doing the reactionary

Close your eyes to where you're bound

And you'll be found

Doing the reactionary

All the best dictators do it

Millionaires keep steppin' to it

The Four Hundred love to sing it

Ford and Morgan swing it

Hands up high and shake your head

You'll soon see red

Doing the reac-

Doing the reac-Tionary

So get in it, begin it

It's smart, oh, so very

To do the reactionary!

The International Ladies Garment Workers Union used the Princess Theatre in New York City as a meeting hall. The union sponsored an inexpensive revue with LGWU workers as the cast and two pianos. Because of their factory jobs, participants could rehearse only at night and on weekends, and initial performances were presented only on Friday and Saturday nights. The original cast was made up of cutters, basters, and sewing machine operators.

Pins and Needles looked at current events from a pro-union standpoint. It was "lighthearted look at young workers in a changing society in the middle of America's most politically engaged city." Skits spoofed everything from Fascist European dictators to bigots in the DAR. Word-of-mouth was so enthusiastically positive that the cast abandoned their day jobs and the production expanded to a full performance schedule of eight shows per week. New songs and skits were introduced every few months to keep the show topical.

According to John Kenrick, Pins and Needles "is the only hit ever produced by a labor union, and the only time when a group of unknown non-professionals brought a successful musical to Broadway."

Originally written for a small theatrical production, the first production of "Pins and Needles" was directed by Samuel Roland. After a two week professional run, it was adapted for performances by members of the then-striking International Garment Workers' Union as an entertainment for its members. Because Roland was associated with left-wing causes, he was asked by ILGWU president David Dubinsky to withdraw. The better-known ILGWU production was directed by Charles Friedman and choreographed by Benjamin Zemach. It opened on November 27, 1937 at the Labor Stage Theatre and then transferred to the Windsor Theatre on January 1, 1939, finally closing on June 22, 1940 after 1108 performances. The cast included Harry Clark, who continued his acting career with roles in The Skin of Our Teeth, One Touch of Venus, Call Me Mister, Kiss Me, Kate, and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?.

The Roundabout Theatre Company produced a revival Off-Broadway at the Roundabout Stage 1 Theatre in 1978, which ran for 225 performances.

The Jewish Repertory Theatre presented a concert in 2003, to include songs and sketches from all versions of the show.

Posted by David Ballela at 6:17 PM 0 comments

Labels: audio, ILGWU, pins and needles

ILGWU Anthem

This comes from a 1965 performance at the 32nd Convention of the ILGWU.

A reference to this anthem is made in Rose Pesotta's Bread Upon The Waters

Posted by David Ballela at 3:46 PM 0 comments

Labels: ILGWU